Venture capital firms looking for new ways to squeeze money out of low-income communities have found a fresh brand of pig lipstick, which they call “income share agreements” or ISAs.

The pushers of the deceptively named ISAs, including venture capitalists from Silicon Valley and the nonprofit Student Freedom Initiative, pitch the instruments as an innovative and healthy, non-debt alternative to America’s burdensome $1.5 trillion student debt load.

They are wrong on both counts. ISAs are certainly a form of debt and may end up costing borrowers even more than a Federally-backed or private loan.

Perhaps the most prominent advocates of ISAs are the folks behind Lambda School, a coding bootcamp that promises to teach students computer coding with no upfront tuition costs. Lambda’s glossy pitch: “You don’t pay tuition until you land a job making at least $50k a year.” Investors in the school include high-profile names like Y Combinator and, well, Ashton Kutcher.

Newcomer billionaire Robert Smith has a similar angle. His nonprofit, Student Freedom Initiative, will offer low interest rate loans to juniors and seniors attending historically Black colleges and universities (HBCU), and majoring in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM)—subjects which on average bring higher earnings. By targeting students with high earnings, Smith believes the “pay it forward” model will make the Student Freedom Initiative sustainable.

But do not be fooled. The Student Freedom Initiative is just a fancy and deceptive name for ISA. Students will not be free from debt but bound to repayments by a contractual obligation.

So how do ISAs work? Instead of taking on the debt upfront, students are obligated upon graduation to devote a portion of their subsequent salary to the investor for a preset period— usually several years. In Lambda’s case, the actual investor becomes difficult to identify because there are so many layers of financing involved. Bloomberg columnist Matt Levine aptly sums up the effect of this system by explaining that “you can securitize people now.”

I do not believe ISAs are a form of indentured servitude. However, despite the use of investment language, I do believe they are akin to predatory lending.

ISAs suffer from a major drawback that prevents potential borrowers from comparing their cost to student loans: a total lack of transparency regarding the amount of future monthly payments and the total repayment. I made this critique about Oregon’s Pay It Forward plan, and the same is true for ISAs.

Purdue University’s “Back-A-Boiler-ISA Fund” is proposed as an alternative to PLUS or private loans. I calculated repayment outcomes for several majors—accounting, civil engineering, economics, English, and philosophy—and it appears that “Back-A-Boiler” has a target return of 50%, that is, $15,000 would be returned to the school for each $10,000 provided to a student.

If a Purdue graduate lands a high-paying job, not only are the monthly payments higher than those for the PLUS loan, but the total repayment amount is higher. The graduate is stuck repaying a big chunk of his or her earnings.

Even worse, the prepayment of ISAs is tied to a fixed return for the investor. But a student who pays off a PLUS loan or private loan early will only repay the interest that has accrued since disbursement. Hence, ISAs ensure benefits to the investor at the expense of the student, which, by definition, is predatory.

Yet defenders of ISAs, like Vanderbilt assistant professor Miguel Palacios, keep pitching the products as innovative and egalitarian. Palacios says what matters is uncertainty about the ability to repay, not the amount to be repaid. He argues that a fixed percentage of your income, whether income is low or high, is better than a fixed payment.

This logic ignores the reality that low-income households spend about 82% of their income on necessities, while high-income households use only 66% of their income for the same expenses. A report by Georgetown University’s Center on Education and the Workforce finds that Black graduates are overrepresented in majors that lead to low earnings. These majors include early childhood education and social work, and prepare students for what the Center refers to as “intellectual and caring professions,” where earnings are often not commensurate with educational attainment. Therefore, the burden of income share agreements will disproportionately affect graduates with lower incomes, who tend to be Black, Hispanic, and Native American—as well as White women—i.e. marginalized populations.

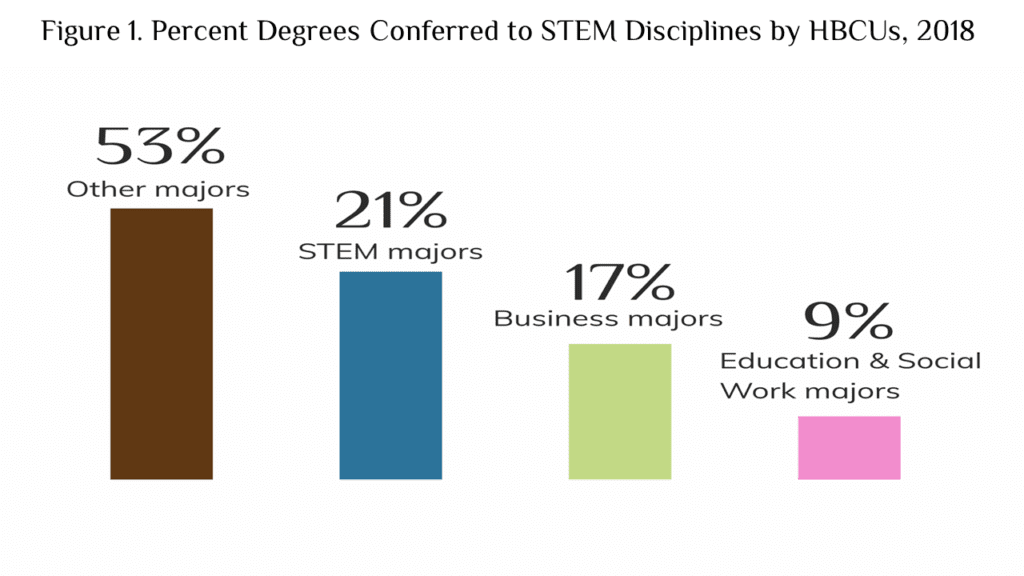

This point is further reflected by a major flaw of the Student Freedom Initiative, in that it targets a small portion of HBCU students. Only 21 percent of HBCU graduates majored in STEM in 2018. Business and related majors (17% of HBCU graduates in 2018) are also high earners. However, 62% of HBCU graduates are in disciplines that are lower paying relative to STEM and business. Even when students of color and White women are employed similarly to White men, there are earnings disparities.

Miguel Palacios, Tonio DeSorrento, and Andrew Kelly argue that missing from the current higher education finance market are instruments that provide information about the returns to majoring in X at institution Y. They posit that ISAs provide information about the value of said investment because investors will only offer ISAs to students attending economically valuable programs, thereby eliminating the risk of accumulating high student debt for low-earning majors.

Because a benefit of ISAs is signaling information about education quality, historically Black colleges and universities, Hispanic serving institutions, minority serving institutions, and women’s colleges may be viewed as low-quality institutions. This false signal ignores the value added by these institutions despite labor market discrimination against their graduates.

The creation of an altruistic fund to provide ISAs to students in less successful majors would reinforce the low-quality signal, not mitigate it. The consequence of ISAs for students of color and White women and the institutions that serve them is not trivial.

By focusing on the economic returns of a major or institution, proponents of ISAs ignore the benefits of a more educated society, like better health care, lower mortality rates, stable employment, control over family size, and more leisure time spent enjoying cultural activities.

In 1998, I wrote my dissertation on higher education financing. The thesis of my dissertation is that a security derivative, an education call option (EdCO), can be used to hedge students against the risk of investing in human capital. What distinguishes my financing scheme from human capital contracts, ISAs, and student loans is that the EdCO can expire worthless, which voids all financial obligations. It is this feature that makes the EdCO useful in attracting students who historically have not had access to higher education.

Policymakers and researchers agree that education debt constrains career choice, homeownership, marriage, and other life choices, as well as limits access to higher education. A truly innovative higher education finance instrument would not only hedge students against the risk of investing in higher education but would broaden access.

If it takes the economy several years to recover from the economic downturn created by the coronavirus pandemic, I fear that supporters of ISA will promote these predatory-lending practices as innovative alternatives to students concerned about their student debt-to-income burden. These students should be sure to compare the total repayment for an ISA to the traditional student loan. The difference is money that could be used to purchase wealth generating assets. Students should also explore income-based repayment options available to a repay Federal or private loan.

Despite the glossy pitches, ISAs and the Student Freedom Initiative are unlikely to improve access to higher education for historically marginalized and financially disadvantaged groups.

Rhonda Vonshay Sharpe is the President of the Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race.