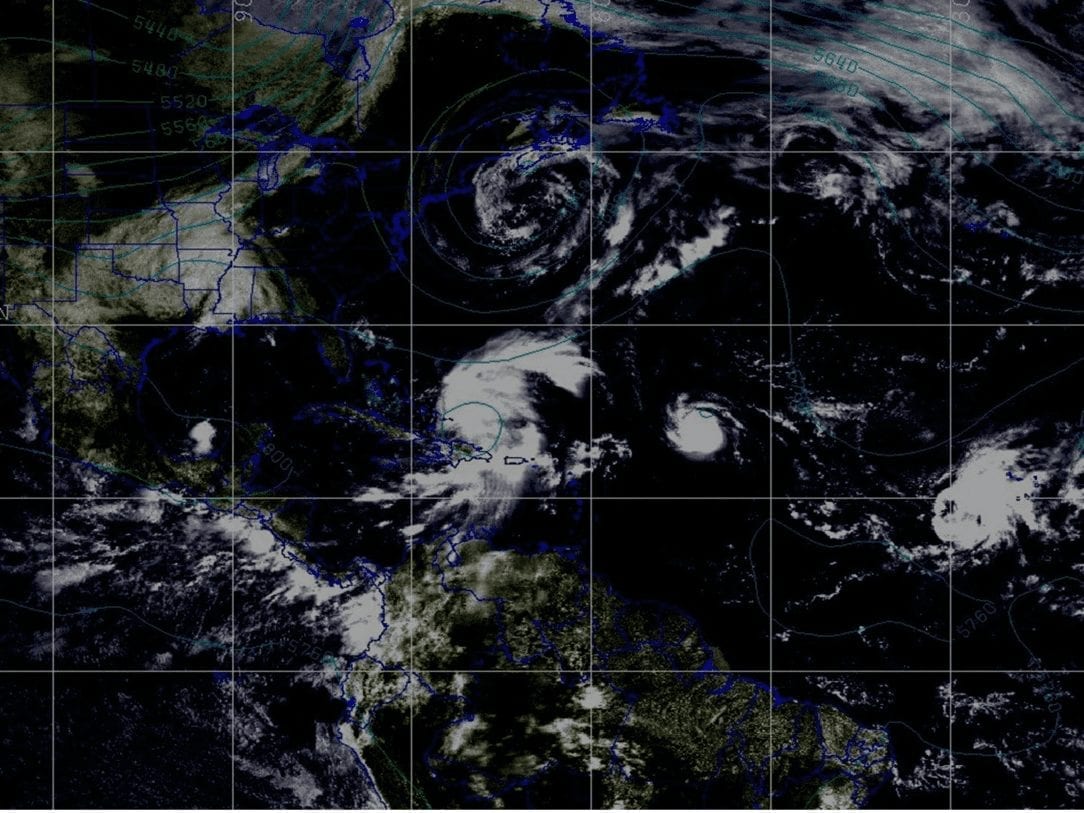

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted nearly every facet of life, including critical hurricane season provisions made by emergency preparedness managers. Forecast models lean toward an Above-Normal 2020 hurricane season (June 1 – Nov 30) in the Atlantic Basin. While emergency preparedness leaders advise citizens to view shelters as a last resort, due to the pandemic, and instead to rely on alternatives such as sheltering-in-place, staying in hotels, or turning to friends/family, those options are not viable for all. As such, many local emergency operation centers are implementing alternative plans and adopting a variety of recommendations from the CDC: added spaces to protect at-risk and elderly residents, an increased number of shelters and decreased number of residents per shelter, social distancing measures, isolation areas for residents showing symptoms of COVID-19, utilization of hotels and dormitories to increase capacity, requirements to wear cloth face coverings, frequent cleaning/disinfecting, COVID-19 testing, changing of cafeteria-style food services, and increased air filtration.

The public is also encouraged to prepare for hurricane season by purchasing critical items (water, food, generators, medical supplies, etc.) and hurricane-proofing homes. However, financial difficulties posed by COVID-19 have limited available resources. Vulnerable populations, like immigrants, have (1) limited resources to allocate towards hurricane preparations at home and (2) increased concerns about using shelters and government resources. It is important to note that undocumented immigrants and those married to undocumented immigrants were excluded from the CARES Act stimulus checks but are not excluded from the dangers of COVID-19 or hurricanes.

A community-approach to hurricane preparedness is necessary to effectively meet the needs of all residents and minimize viral spreads. Historically, foreign-born residents have described elevated concerns during hurricane seasons. A 2018 study on immigrants residing in the 24 counties of the Texas Gulf Coast region found: “compared to native-born citizens, immigrants in these Texas counties report[ed] more tenuous financial and social circumstances,” including higher proportions of incomes under 200% of Federal Poverty Level, decreased levels of health, home, and flood insurance, and few relatives/friends nearby to rely on in difficult times. “For a variety of reasons, including potential language barriers, lack of social ties, and fears of drawing attention to their own or someone else’s legal resident status, immigrants may be more vulnerable to the effects of natural disasters and their aftermath compared to those who were born in the United States.”

Roughly six million immigrants hold frontline positions. Many of these occupations, healthcare aides and maids and housekeeping cleaners, disproportionately hire women. Higher status jobs that have the option to telework are limited for immigrants, especially immigrant women. Immigrant women from Latin American countries are the least likely to be college graduates and immigrants, in general, are more likely to lack a high school education. The occupational segregation of immigrant women puts them at greater risk of contracting/spreading COVID-19 to their families. Additionally, many immigrants reside in overcrowded, multigenerational residences, and send remittances to family outside the country, which limits their ability to afford safe shelter during hurricane season.

While many studies highlight COVID-19’s impact on undocumented immigrants, President Trump’s “Public Charge Rule,” paired with hurricane season and the pandemic, creates concerns for immigrants on legal immigration pathways. The Public Charge Rule determines “whether someone is likely at any time in the future to become a public charge,” which could be used against that person when pursuing green card status. Opponents cite its harming of efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19 because it dissuades some immigrants from getting tested/treated out of concern it will negatively impact their chances of obtaining a green card. Despite the assurance that “individuals seeking medical treatment for the virus should continue to do so without fear or hesitation,” some immigrants worry that utilizing services could flag them as a “public charge” and make them ineligible.

The complexity of a pandemic during hurricane season will increase the health and economic vulnerability of immigrant women and their families. As Congress debates the who, when, and how much for the next coronavirus aide package, we must ask that they include relief for immigrant workers who perform jobs that are essential to the American economy.

By Ashley Zehrt is a research assistant and doctoral student at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University.

Rhonda Vonshay Sharpe is the President of the Women’s Institute for Science, Equity and Race.